Optimising Hydration for Health & Performance

Optimising Hydration for Health & Performance

Optimising Hydration: Introduction

If you ask the majority of people what the most important nutrient is, they are likely to identify one of the macronutrients, such as protein, fat, or carbohydrate. Few, if any, are likely to say water. Yet while some debate exists reading how long we can survive without food, with estimates suggesting as long as 70 days in some cases, there is no such debate when it comes to surviving without water; that is 3-5 days.

Consequently, water has been called the ‘most essential’ nutrient, and not only for health. It is also the most important nutritional ergogenic aid for athletes, as maintaining hydration during exercise is one of the most effective ways to maintain performance. Despite its importance, water is also referred to as a forgotten, neglected, and under-researched nutrient.

People involved in demanding exercise often pay great attention to their nutrient intake in terms of how much and when to consume protein, fats, and carbohydrate and perhaps certain vitamins and minerals, and may even supplement when they feel necessary. Yet when it comes to hydration, they often just rely on their thirst as an indicator of when and how much fluid they should consume. However, thirst is not typically triggered until we are already dehydrated by approximately 1-2% at which point, various aspects of cognitive and physical performance can already be hindered, and if sustained long enough, can lead to a variety of health problems. Consequently, maintaining optimal hydration levels not only helps to improve health, but also maximise performance.

Understanding Hydration

A term commonly associated with hydration is ‘water balance’. This refers to the equilibrium between the intake and loss of water in the body. It depends on the net difference between water we gain primarily from drinking fluids and eating foods with high water content and the water we lose each day through urine production, sweat, evaporation from the respiratory tract through breathing, and faeces (1). Interestingly, the body can actually produce water, which is known as metabolic water, but it is only a small amount, in the region of approximately 0.25 to 0.35 litres per day (1).

The process of maintaining water balance is described as ‘hydration’. The state of optimal hydration, where the body’s water balance is maintained at ideal levels is known as ‘euhydration’. The term “hypohydration” refers to a reduced level of water in the body beyond the normal range while “hyperhydration” refers to a general excess of water beyond the normal range. ‘Dehydration’ describes the process of losing body water and “rehydration” describes the process of gaining body water (2).

It is important to note that hypohydration and dehydration are often used interchangeably, although they have distinct meanings in the context of hydration. Throughout this article we will use the term ‘dehydration’ to describe a reduced level of water as this is more commonly used in many scientific papers and is likely to be more familiar to the reader.

The maintenance of body water balance is so critical for survival that the volume of water in the body is defended rigorously within a narrow range, even when there is a large variability in our daily water intake (1). The body has a number of mechanisms to achieve this. These include adjustments in urine production by the kidneyS to conserve or expel water and the release of hormones such as anti-diuretic hormone (ADH), which increases water reabsorption in the kidneys, reducing urine output and helping the body to retain water.

The average daily water turnover, i.e., the amount of water that enters and leaves the body in a 24-hour period, is approximately 3.6 litres. For women, this is 2.8 to 3.3 litres and for men, 3.4 to 3.8 litres (1). We have a limited capacity to store water, so any water losses must be replaced daily.

Why Water is So Important

To really understand how important water is, we need to understand a little of what it does in the body. Firstly, water is the single most abundant chemical found in living things and is the largest constituent of the human body, which is about 70% water by weight. It is essential for life and is involved in virtually all functions of the body.

These include:

- Transport: Water acts as a carrier, transporting nutrients and oxygen to cells and removing waste products. Blood, which is essential for cardiovascular function and the transport of oxygen, nutrients and waste products, is 80% water.

- Digestion: Water is vital for digestion and the absorption of nutrients. It helps break down food and allows the body to absorb essential vitamins and minerals.

- Detoxification: Water aids the flushing out of toxins and waste products through urine and sweat.

- Joint lubrication: Water helps to keep joints lubricated, reducing friction and preventing joint pain and injury.

- Cell Function: Every cell in the body depends on water for normal function, as it is involved directly in countless biochemical reactions.

- Temperature Regulation: Water helps regulate body temperature through sweating and respiration.

The Dangers of Dehydration

The term ‘dehydration’ tends to conjure up images of someone in a desert with parched lips attempting to draw the last drips of water from an empty bottle. Although a person in that situation is likely to be dehydrated, such cases are rare and extreme. The reality is that the negative consequences of suboptimal hydration can occur more subtly and with a less drastic loss of water. The normal daily variation of body water is less than 2% body mass loss. Consequently, hypohydration, or dehydration, is clinically defined as a 2% or greater loss of body mass (2). Even at this level, health and performance can be negatively affected, with the effects becoming more pronounced and potentially damaging as water levels decrease until the loss reaches 9-12%, when death can occur (3).

The Effects of Hydration Status on Health

Dehydration can have adverse effects on a number of aspects of health. These include:

- Cognitive performance: Dehydration impairs cognitive performance for tasks involving attention, memory, executive function (i., attentional control, working memory, inhibition, and problem-solving), reaction time, and motor coordination when water deficits exceed 2%.

- Mood and fatigue: Dehydration is associated with increased negative emotions such as anger, hostility, confusion, depression and tension, as well as fatigue and tiredness.

- Kidney function: Chronic dehydration can increase the risk of kidney stones and other kidney-related issues. On the other hand, there is a significant association between high fluid intake and a lower risk of kidney stones.

- Cardiovascular health: Dehydration can affect cardiovascular function, leading to increased heart rate and reduced blood pressure. This can put additional strain on the heart, especially during physical activity.

- Digestive health: Maintaining adequate hydration is crucial for proper digestion and bowel function, as dehydration can cause constipation and other gastrointestinal issues.

- Body weight and composition: Increased water consumption contributes to reductions in body fat and/or weight loss in obese adults, independent of changes in energy intake.

The Effects of Hydration Status on Exercise Performance

The general consensus is that exercise performance can be significantly impaired when 2% or more of body weight is lost through sweat (3,4,5). For example, this would be a loss of just 1.4 kg body weight for a 70-kg athlete. Furthermore, weight loss of more than 4% of body weight during exercise may lead to heat illness, heat exhaustion and heat stroke, which if severe enough or not treated, can be fatal. This may seem extreme, but athletes commonly lose 1-6% of their body weight of body weight during intense exercise (3).

It is important to note that while some athletes might tolerate body water losses amounting to 2% of body weight without significant risk to physical well-being or performance when the environment is cold or temperate, when exercising in a hot environment, such a water loss not only impairs absolute power production, but also predisposes individuals to heat injury (5).

A study by Lopez et al., (6) investigated the influence of hydration status on physiological responses and running speed in the heat. The results showed that those runners who were dehydrated produced slower run times, and experienced greater perceived effort and increases in core temperature in comparison to well hydrated subjects.

A number of physiological changes that affect performance are associated with dehydration.

These include:

- A decrease in blood volume

- A decrease in cardiac output

- An increase in heart rate

- A decrease in aerobic capacity (VO2max)

- A decrease in anaerobic capacity

- A decrease in lactate threshold

- A decrease in electrolytes

- A decrease in sweat rate and delayed onset

- A decrease in the buffering capacity of blood

- A decrease in blood flow to skin

- A decrease in attention and focus

The effects of these on performance typically include reduced exercise time to exhaustion, reduced total work capacity and reduced speed of movement (3).

The Effects of Hydration Status on Muscular Strength and Performance

The scientific literature relating to exercise and hydration tends to focus on the effects of endurance type exercise. Less well acknowledged are the effects of dehydration on muscular performance, and yet they can also be significant (7,8,9).

For example, a study by Judelson et al., (7) found that dehydration appears to reduce strength by approximately 2%, power by approximately 3% and high-intensity endurance (maximal activities lasting longer than 30 seconds but less than 2 minutes) by approximately 10%.

Another study (9) found a similar effect with dehydration impairing muscular endurance by 8.3 %, strength by 5.5% and anaerobic power by 5.83%.

Although it is easy to see how a relatively low level of dehydration can affect endurance performance, particularly in hot weather, less obvious is how poor hydration can impede muscular strength and performance. A number of mechanisms have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, including changes in cardiovascular and metabolic functions and the neuromuscular system (7). Motor skills, reaction time, and coordination all contribute to performance and deteriorate when water deficits exceed 2% (2).

While a figure of approximately 2% of bodyweight water loss is commonly cited as the point at which muscular performance becomes negatively affected, it is important to note that this may not be the same across all age groups. For example, dehydration of as little as 1% has been shown to impede muscular endurance, power, and strength in men in their 60s (10).

The Effects of Hydration Status on the Anabolic Response to Resistance Training

Evidence suggests that our hydration levels not only affect our muscular performance, but can also have a negative impact on our gains by altering the hormonal response to training.

Judelson and colleagues (11) found that dehydration increased the release of the catabolic hormone cortisol in response to resistance training and impeded the body’s anabolic response by reducing testosterone. A loss of body mass of just 2.5% resulted in a 10.8% reduction in testosterone. When dehydration increased to 5% there was an accompanying 16.8% decrease in testosterone. The authors suggest that combined with evidence documenting the negative effect of dehydration on muscular performance, these findings indicated that individuals who routinely complete resistance training in a dehydrated state may diminish their overall training adaptations.

Research shows (12) that when athletes rely on thirst alone, they do not drink enough fluid voluntarily to prevent dehydration during exercise. This is exacerbated by the fact that the majority of athletes begin training or competition in a somewhat dehydrated state.

Too Much of a Good Thing: The Dangers of Hyperhydration

In any discussion on hydration, the focus tends to be on the problems associated with insufficient water intake, and with good reason. However, hyperhydration, i.e., a general excess of water beyond the normal range, can also be problematic and potentially life threatening.

Overhydration, also known as water intoxication, typically occurs when more water is consumed than the kidneys can remove. It is most common among endurance athletes who drink large amounts of water before and during exercise, such as during a race. It has also been reported in military personnel during training and hikers. Individuals with kidney or liver disease or those suffering from heart failure also have an increased risk.

Overhydration is associated with a number of key issues. These include

- Electrolyte imbalance: Drinking too much water can dilute the electrolytes in the body, particularly sodium. Electrolytes are essential minerals that carry an electric charge. These are crucial to a number of functions, including maintaining fluid balance, blood pressure, nerve function, muscle contraction, and acid-base balance (pH), all of which are important for health and performance. When blood sodium levels are low, this is known as hyponatremia. It can cause cells to swell with excess water, leading to various symptoms ranging from mild to severe such as brain swelling, resulting in seizures, coma, and even death.

- Kidney overload: Overhydration can overwhelm the kidneys’ ability to excrete excess water, leading to water toxicity.

- Muscle cramps and weakness: Dilution of electrolyte and imbalances can cause muscle cramps, weakness, and spasms.

- Increased urination: Excessive water intake can lead to frequent urination, disrupting daily activities and sleep.

Determining Hydration Status

We have seen how too little or too much water in the body can problematic, which brings us to how we can determine our ideal level of hydration. There are various methods that can be used for this, ranging in complexity and expense from simply monitoring changes in body weight before and after training to laboratory tests, which involve the analysis of blood or urine.

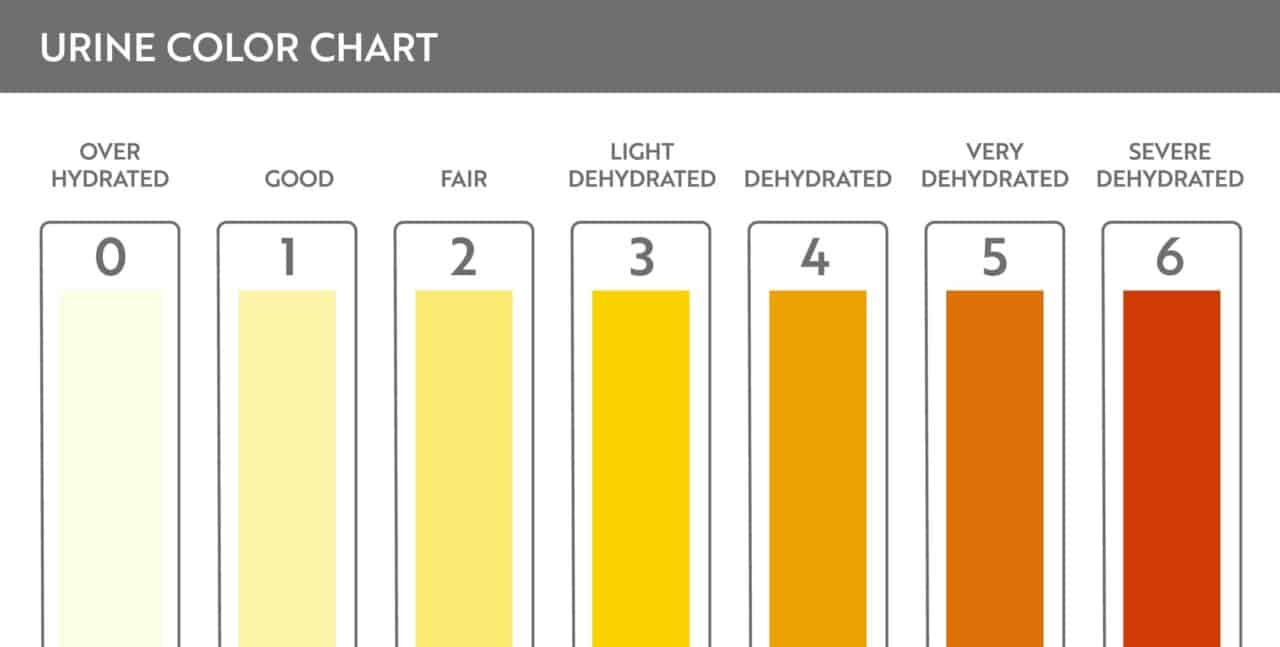

The easiest and most convenient method is to monitor the colour of your urine. According to the NHS, in a healthy person, pale yellow urine that looks like lemonade indicates that you are appropriately hydrated, and this should be your goal (13). Darker urine indicates a level of dehydration requiring an increased fluid intake. For example, dark yellow suggests mild dehydration while brownish colour could indicate severe hydration. On the other hand, if your urine is colourless, rather than pale yellow, this indicates that you are overhydrated.

It is important to note that changes in urine may be indicative of health problems requiring further investigation. For example, reddish or pink urine could be a sign of blood. Therefore, it is important to monitor the colour of urine and seek medical advice should you notice any inexplicable changes.

Also, be aware that certain foods, medications, and supplements can also affect urine colour.

Achieving Optimal Hydration: How Much Do We Need to Drink?

As with other essential nutrients, there are guidelines regarding fluid intake. The NHS recommends that we consume 6 to 8 cups or glasses of fluid a day (13). As a glass is typically around 240 ml, 6-8 glasses would provide approximately 1.44 to 1.92 litres. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), on the other hand, recommends 2.0 litres per day for females, and 2.5 for males (14).

However, it important to note that these figures are very general and unlikely to satisfy the fluid needs of many athletes when you consider that during high intensity exercise in hot conditions, sweating and respiratory evaporation can result in a water loss as great as 2-3 litres per hour!! (3).

In light of this, both authorities suggest that fluid intake may need to be increased in certain circumstances.

So how much do you need to drink if you engage in demanding exercise and in hotter temperatures? Remember, even in Britain, summer temperatures often reach the high twenties and low thirties.

The International Society of Sports Nutrition (4) suggest that it is critical that athletes adopt a mindset to prevent dehydration first by promoting optimal levels of pre-exercise hydration. Throughout the day and without any consideration of when exercise is occurring, a key goal is for an athlete to drink enough fluids to maintain their body weight.

Next, athletes should strive to start exercise well hydrated, which can be achieved by keeping thirst sensation low and urine colour clear pale yellow (15). Therefore, optimal pre-exercise hydration can be achieved by ingesting 500 mL of water or sports drinks the night before a competition or demanding training session, another 500 mL upon waking and then another 400–600 mL of cool water or sports drink 20–30 min before the onset of exercise.

Once exercise begins, the athlete should strive to consume a sufficient amount of fluid to maintain hydration status. As a guide, this would be around 0.5 to 2 litres of fluid per hour to offset weight loss. This should be broken down to small amounts consumed every 5–15 mins. It is important to note that fluid should not be ingested at rates in excess of sweating rate, as body water and weight should not increase during exercise (5).

Post-exercise the aim is to rehydrate, i.e., completely replace lost fluid and electrolytes during the training session or competition. Weighing yourself immediately before and after exercise will allow you to monitor changes in fluid balance. You can then work out how much you need to consume to replace any losses. Generally speaking, it is recommended that we consume 125-150% of the fluid lost during exercise (4). This means, for example, if you lose 1 kg of body weight (which equates approximately to 1 litre of fluid), you should aim to drink about 1.25 to 1.5 litres to rehydrate fully.

We know how much to drink but what should we drink to optimise hydration?

What is the Best Hydration Drink?

As the importance of water for health, performance and the maintenance of life itself is indisputable, and it is generally recommended that water make up the majority of our fluid intake, it would therefore be reasonable to assume that consuming plain water is the best choice for optimising hydration. However, while water may suffice for a relatively short workout in a moderate environment, this is not always the case. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) (17) guidance on hydration for ultra distance endurance athletes suggest a major consideration to what kind of fluid an athlete should consume is whether the beverage is providing a sufficient amount of electrolytes.

This is because although the main component of sweat is water, it also contains various electrolytes, mainly sodium, chloride, potassium, calcium, and magnesium. These play a vital role in numerous processes essential for good health and optimal performance such as muscle function and maintaining fluid balance. In fact, fluid balance depends on electrolyte balance, and vice versa (3).

When large amounts of water are lost from the body, such as during exercise, the balance between water and electrolytes can be disrupted quickly.

If you are training hard, sweating heavily, drinking copious amounts of plain water to replace your water losses, this can result in a dilution of electrolytes. As we have seen, in the case of sodium, if the dilution is sufficiently great, it can result in the potentially life-threatening condition, hyponatraemia.

Unfortunately, many athletes commonly consume insufficient fluid and electrolytes just prior to, or during training and competition (12), which, although may not result in a life or death situation, can impede performance.

This is where Time 4 Hydration can make a valuable contribution to your hydration strategy,

What are the Benefits of Time 4 Hydration?

The ingredients in Time 4 Hydration have been shown scientifically to aid hydration and performance in a number of ways. These include, but are not limited to:

- Enhancing whole body fluid balance (17,21,25,16)

- Enhancing electrolyte balance (32,12,17,16)

- Promoting rehydration (18)

- Enhancing nutrient absorption (17)

- Enhancing recovery (16,27)

- Improving exercise performance (12, 16, 22,27)

- Supporting kidney function (32)

- Supporting muscle function (34,17)

- Reducing fatigue (16,33,34)

- Reducing muscle cramps (36)

- Reducing exercise-induced gut damage and permeability (19,20,24)

What’s in Time 4 Hydration?

Time 4 Hydration contains a potent combination of 6 evidence-based substances designed to enhance hydration and optimise performance and recovery. These include, Sodium Chloride, Calcium Phosphate Anhydrous, Potassium Sulphate and Magnesium Chloride, L-Glutamine and L-Glycine.

As we look at each of these ingredients in-depth and the research that supports their use, you’ll begin to see why Time 4 Hydration is such a great product and how it may benefit you.

What is Sodium Chloride?

Sodium chloride is a compound made up of the mineral sodium and the element chlorine. It is commonly known as ‘halite’ when it occurs in nature and is often referred to as rock salt.

When dissolved in water, sodium chloride separates into sodium ions and chloride, both of which are essential electrolytes in the body, and are the most abundant electrolytes in sweat.

Sodium plays a vital role in many processes. These include the absorption and transport of nutrients (including other electrolytes, amino acids, glucose), control of the acid–base balance, the maintenance of blood volume and pressure, fluid balance, nerve function, and muscle contraction. It enhances the body’s ability to retain water and helps to prevent muscle cramps and maintain performance during prolonged physical activity.

Chloride also helps to maintain the body’s fluid balance, and contributes to the function of nervous and muscular systems, and the formation of stomach acid needed for digestion.

The Benefits of Sodium for Hydration and Performance

Including Sodium in sports drinks has been shown to provide a range of benefits, including the maintenance of electrolyte concentrations, which in turn can help to preserve neuromuscular coordination and power output, increased thirst and reduced urine output, which help to maintain whole body fluid balance, and enhanced glucose absorption from the gut, which helps to fuel working muscles (17)

A number of studies have shown how these effects contribute to enhanced performance. Ayotte and Corcoran (12) found that maintaining hydration and Sodium levels improves anaerobic power, attention and awareness, and heart rate recovery time in athletes engaged in demanding exercise. The authors noted that unlike non-athletes or athletes who do not engage in frequent rigorous and prolonged training sessions, ‘hard trainers’ may require additional Sodium and benefit more from a hydration plan tailored to their individual needs.

Consuming Sodium containing drinks has also been shown to be highly effective at enhancing rehydration after exercise. The results of a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind clinical trial, considered to be the ‘gold standard’ in research, showed that consuming a Sodium containing beverage resulted in a greater suppression of urine production and promoted greater rehydration than water alone in athletes who were dehydrated by 2.6% body mass loss after a 90-minute training session (18).

What is Calcium Phosphate Anhydrous

Approximately 99% of the body’s calcium is stored in the bones, with remaining 1% present in other cells, including muscle cells.

Phosphorus is the second most abundant mineral in the body after calcium. It plays an essential role in the development of strong teeth and bones. It is also involved in the function of the nervous and cardiovascular systems, energy production, the growth, maintenance and repair of tissue and cells, and protein synthesis.

Calcium phosphate has several advantages over regular calcium supplements. Unlike calcium carbonate, it is less likely to cause digestive issues; it provides the dual benefit of both calcium and phosphorus; and it is stable and does not react with stomach acid, making it the preferred option for people with low stomach acid.

The Benefits of Calcium Phosphate Anhydrous for Hydration and Performance

Along with other electrolytes, such as sodium and potassium, calcium helps to prevent dehydration and maintain proper hydration levels in a number of ways. Firstly, it acts as an important signalling molecule which helps to regulate the movement of fluid in and out of cells. This includes the movement of water and electrolytes across cell membranes, helping to maintain proper fluid balance within tissues. Calcium also supports kidney function, which is crucial for fluid filtration, absorption, and balance. Disturbances in calcium levels have been linked to various kidney disorders including chronic renal insufficiency, a condition where the kidneys gradually lose function over time, and kidney stones (32).

While calcium is vital for exercise performance exercise through its roles in muscle contraction, energy production and hydration, exercise appears to increase calcium losses. A study by Dressendorfer (31) investigated the effects of training on blood and urinary minerals levels. The results showed that high-intensity interval training led to increased renal calcium excretion and a decrease in blood calcium levels below the clinical norm.

It is important to note that although muscle cells can draw on the vast reserves of calcium stored in the bone tissue, an inadequate calcium intake and increased calcium losses may increase the risk of osteoporosis. Young women involved in weight-control sports, such as figure skating and distance running, who may have inadequate dietary intake of calcium are particularly at risk (4).

What is Potassium Sulphate?

Potassium sulphate is a chemical compound composed of the essential mineral potassium, sulphur, and oxygen.

Potassium is an important electrolyte needed by every cell in the body for normal function. It plays a vital role in numerous processes required for good health and exercise performance. These include maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, nervous system and cardiac function, control of blood pressure, and muscle contraction.

Despite its importance, most people do not consume sufficient potassium in their diet. In the UK, the average intake is around 2,000 mg per day, which is below the recommended 3,500 mg (35). Lower potassium consumption has been associated with elevated blood pressure, hypertension, and stroke. While higher levels have been shown to help protect against these conditions. For example, higher potassium intake was associated with a 24% lower risk of stroke (35).

The Benefits of Potassium Sulphate for Hydration and Performance

Potassium sulphate benefits hydration primarily through its potassium content. It works in conjunction with sodium to regulate the body’s hydration levels, which it does by controlling the balance of fluids inside and outside cells, ensuring cells remain properly hydrated. This is vital for overall performance and recovery, and helps to ensure normal muscle function by preventing muscle weakness, fatigue and cramps, which can be common during prolonged and demanding exercise. Loss of potassium in muscle has been cited as a major contributing factor to muscle fatigue (33,34) and may also contribute to the pain and degenerative changes seen with prolonged exercise (33).

A review by Lindinger et al., (34) highlighted the importance of potassium for muscle performance and health. The results showed that muscle and blood plasma levels of potassium are altered markedly during and after high-intensity dynamic exercise and static contractions which have implications for skeletal and cardiac muscle performance. Moderate elevations of potassium during exercise have beneficial effects on multiple physiological systems. On the other hand, severe reductions in the muscle cell likely contributes to muscle and whole-body fatigue, leading to impaired exercise performance. The authors also noted that chronic or acute changes in blood potassium, both too high or too low can have dangerous health implications for cardiac function.

What is Magnesium Chloride?

Magnesium is an essential mineral found in all human tissues, especially bone. It plays an important role in the replication of DNA, the secretion of parathyroid hormone, which controls bone calcium levels, the function of muscle tissue and the nervous system, and energy production. It also contributes to protein synthesis, electrolyte balance, psychological function and the reduction of tiredness and fatigue.

Magnesium chloride is formed by combining magnesium with chlorine, making a stable and highly soluble compound. This stability is beneficial for consistent dosing and absorption when used in supplements or hydration drinks. The chloride part of the compound aids the absorption of Magnesium in the body. Chloride ions help create the right environment in the stomach and intestines, promoting better uptake of magnesium ions. When combined with magnesium, chloride contributes to overall electrolyte balance.

Like potassium, the typical Western diet is often low in magnesium.

The Benefits of Magnesium Chloride for Hydration and Performance

Magnesium Chloride works with other electrolytes to maintain proper hydration levels by replenishing those electrolytes lost in sweat, which helps to maintain muscle function and avoid cramps.

At a cellular level, magnesium helps to stabilise cell membranes, making them more permeable to water. This allows water to move more easily into and out of cells, ensuring proper hydration. Magnesium also moves calcium and potassium ions across cell membranes, which is essential for muscle and cardiac function.

Despite the fact that many athletes, particularly endurance athletes suffer from muscle cramps and soreness during marathon events, magnesium is not as common as other electrolytes such as sodium in sports drinks.

Kharait (36) investigated the effects of adding Magnesium to an electrolyte drink on the incidence and severity of muscle cramps during a half marathon race. Participating athletes consumed either magnesium-rich electrolyte mix or water for hydration. The results showed that amongst the athletes who consumed only water, approximately 46% had muscle cramps compared to 21% in those who hydrated with the Magnesium mix.

Further analysis shows that the Magnesium mix reduced the incidence of both, mild-moderate as well as severe muscle cramps. Mild-moderate muscle cramps occurred in just 12% of athletes who hydrated with Magnesium compared to 26% in those who consumed water. The incidence of severe muscle cramps was reduced from 20% to 9%.

What is Glutamine?

You may be familiar with glutamine, as it is the most abundant amino acid in the human body. It makes up approximately 60 percent of our skeletal muscle. It is well known for its ability to reduce muscle soreness and enhance recovery by supporting protein synthesis and reducing muscle breakdown.

Muscle tissue is a major site of glutamine production, where it forms the anabolic precursor for muscle growth. It is referred to as a ‘conditionally essential amino acid’. This means that although the body can synthesise it from other amino acids, under certain conditions, such as illness, surgery and periods of intense training, the glutamine needs of our body may exceed its ability to produce it and so it must be obtained from dietary sources.

Less well known is glutamine’s role in gut health. It supports the gastrointestinal tract by maintaining gut barrier integrity to prevent gut permeability, reducing inflammation, and aiding nutrient absorption. It also helps to protect against exercise-induced digestive issues, and supports immune function, particularly in the vulnerable post-workout period.

The Benefits of Glutamine for Hydration and Performance

Glutamine aids hydration in a variety of ways: Firstly, by supporting a healthy gut barrier it ensures efficient absorption of nutrients, including water and electrolytes. It also supports kidney function by aiding the excretion of nitrogen and ammonia, which can affect electrolyte balance and overall health.

Although exercise has numerous benefits for health, it is also associated with a variety of gastrointestinal issues. In fact, symptoms are so common amongst athletes engaging in strenuous exercise that they are now considered to be a medical condition, referred to as ‘Exercise Induced Gastrointestinal Syndrome’. This is characterised by a series of gastrointestinal disturbances that affect the physical and psychological performance of athletes (28). These are particularly prevalent when exercising in increased environmental temperatures, at higher intensities, or for very long durations (29). Various factors are believed to be responsible, such as damage to the cells of the lining of the gut and an increase in gut permeability (28,29). This can result in disruption of nutrient absorption, including water and electrolytes. One study found that just a single bout of exercise increases gut damage and permeability in healthy participants, which is exacerbated in hot environments (23).

A review by Chantler and colleagues (19) investigated the effects of various of dietary supplements, including glutamine, on exercise-induced gut damage and permeability. Twenty-seven studies were included in the review. The results showed that the majority of studies using glutamine demonstrated a reduction in markers of gut cell damage and permeability compared to a placebo

The results of another review (20) showed that glutamine is able to modulate intestinal permeability in several gut-related conditions including irritable bowel syndrome. It also demonstrated Glutamine’s ability to improve gut barrier function in both experimental and clinical situations.

Glutamine not only helps hydration through enhanced gut integrity, but also has a more direct effect.

Van Loon and colleagues (21) found that supplementation with glutamine reduced net water secretion and net sodium secretion. The authors suggest that glutamine offers considerable benefit, as it is able to both stimulate water absorption and maintain healthy gut function.

Glutamine’s positive effect on hydration has been shown to directly improve exercise performance. The results of a study by Hoffman et al., (22) showed that consuming a supplement containing glutamine prior to exhaustive exercise provided a significant ergogenic benefit by increasing time to exhaustion in subjects who were dehydrated by 2.5% of body mass. The authors suggest that the ergogenic effect was likely due to an enhanced fluid and electrolyte uptake.

What is Glycine?

Glycine is an amino which plays an important role in many processes. These include protein synthesis (constitutes 1/3 of amino acids in collagen and elastin), reducing muscle wasting, the formation of creatine, which supports energy production for high intensity exercise, production of the master oxidant glutathione, improving heart health, and enhancing sleep. It has been shown to enhance the absorption of the essential amino acid, Leucine, which provides the signal to switch from a catabolic state, in which muscle tissue is being broken down, to an anabolic state in which it begins to rebuild.

Like glutamine, glycine is not an essential amino acid, but is considered to be ‘conditionally essential’. In fact, there is evidence that it is almost impossible to satisfy our daily requirements for glycine even from food alone (24), particularly when engaging in demanding exercise. Hence the benefit of supplementation.

The Benefits of Glycine for Hydration and Performance

Glycine contributes to hydration via a number of mechanisms. For example, it has humectant properties, which means it attracts and retains moisture. This is particularly relevant to hydration of the skin. In a number of physiological processes, glycine functions as an organic osmolyte, which means it helps regulate cell volume by balancing the movement of water in and out of cells (30).

It also plays an important role in metabolic regulation, anti-oxidative reactions, and neurological function (25), all of which influence hydration. Proper metabolic regulation ensures that cells receive the necessary nutrients and water to stay hydrated. Glycine acts as a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, which can influence various bodily functions, including fluid balance and hydration. It also contributes to the production of glutathione, a powerful antioxidant that helps to protect cells from oxidative stress, which can cause damage. This can lead to dehydration, as cells lose their ability to regulate water and electrolyte balance effectively. Dehydration itself can exacerbate oxidative stress, creating a vicious cycle (26).

Glycine also plays an essential role in enhancing gut health and reducing permeability. The gut has several types of membrane transport systems which use glycine to enable the cellular uptake of various substances (24).

A review by Razak and colleagues (24) highlight a number of ways in which glycine supports and promotes gut health. These include protecting against various forms of intestinal injury, helping to combat oxidative stress, and reducing inflammation.

While the primary reason for glycine’s inclusion in Time 4 Hydration is to enhance hydration, science has demonstrated its many benefits for health and performance. For example, glycine has been used to prevent tissue injury, enhance anti-oxidative capacity, promote protein synthesis and wound healing, improve immunity and treat metabolic disorders in obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, and various inflammatory diseases (25).

When it comes to performance, there is evidence to indicate that glycine supplementation may enhance peak power output, reduce lactic acid accumulation during high-intensity exercise, and improve sleep quality and recovery (27).

Synergy: The secret of Time 4 Hydration

All of the ingredients in Time 4 Hydration have been carefully selected based on the scientific evidence demonstrating their ability to improve hydration and support performance. Although a number of these ingredients target different physiological mechanisms, they also work together to produce a synergistic effect; i.e., one which is greater than the sum of their separate effects.

While sodium and chloride are the most abundant electrolytes in sweat, which is why Time 4 Hydration provides 1.3g of sodium chloride per serving, potassium, calcium and magnesium are also found, albeit in lower amounts, with each one making an important contribution to hydration and performance. For example, potassium works with sodium to maintain several crucial important functions in addition to fluid balance, such as nerve transmission and muscle contraction.

Studies show that replacing electrolytes lost in sweat not only helps to maintain hydration, but also improve exercise performance.

Choi and colleagues (16) compared the effects of plain water consumption and an electrolyte drink containing sodium, potassium and magnesium, on exercise capacity and recovery after exhaustive exercise. The results showed that consumption of the electrolyte drink increased the body’s capacity to retain water, improved exercise ability and recovery, and reduced exercise-related fatigue compared to water alone.

The addition of the amino acids glutamine and glycine sets Time 4 Hydration apart from other electrolyte drinks, as they not only further enhance hydration but also support the absorption of electrolytes and help to protect against exercise induced gut damage.

It is this synergism that makes Time 4 Hydration greater than the sum of its parts.

Optimising Hydration: Summary

The importance of optimal hydration for health and performance is indisputable. Yet of all of the nutrients, water gets the least consideration. People engaged in demanding exercise often just rely on their thirst as an indicator of when and how much fluid they should consume. However, thirst is not typically triggered until we are already dehydrated by approximately 1-2% of body mass. Even such an apparently minor reduction of just 2% can inhibit endurance and result in a loss of strength and power, and cause premature fatigue. It can also impair cognitive function, resulting in poorer attention, reaction time and decision-making skills, increase the risk of injury and impair post-exercise recovery. This situation is made worse by the fact that we do not tend to enough fluid voluntarily to prevent dehydration during exercise, which is further exacerbated by the fact that the majority of athletes begin training or competition in a somewhat dehydrated state.

While water is essential, it does not mean that plain water is the most effective hydration drink. This is because the body not only loses water, but also electrolytes, which if not replaced, can have a range of potentially detrimental effects.

This is where Time 4 Hydration can play a valuable role in your hydration strategy, as it provides the electrolytes lost in sweat and at a level shown to be beneficial while avoiding the problems associated with overconsumption. Time 4 Hydration also benefits from the addition of glutamine and glycine to further enhance fluid balance and aid electrolyte absorption and gut integrity.

Hydration may be the neglected component of nutrition, but if you give it the attention it deserves, it will provide you with a host of benefits for both your health and performance.