BODY POSITIVITY VERSUS SCIENCE – BEAUTY IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER, HEALTH IS NOT

Body Positivity Versus Science

Body Positivity Versus Science – Beauty Is In The Eye Of The Beholder, Health Is Not

(Click on Links in Blue for More Info)

Canadian psychologist, YouTube personality, author, and academic, Dr Jordan Peterson recently caused something of a stir by commenting “Sorry. Not beautiful” on Twitter in response to Sports Illustrated showing an obese model in their swimwear issue, which traditionally features very slim, athletic models.

If you watch the YouTube interview where Mikhaila Peterson sits down for a discussion with her father, Jordan Peterson, in which he discusses his statement, it is clear that rather than attacking and belittling obese people, Peterson is making a broader comment on the way in which the media callously manipulate our idea of health and beauty for their own gains, rather than for altruistic reasons, such as the promotion of diversity and inclusion.

Regardless of what you think of Peterson and his comment, he does help to highlight the confusing and contradictory times in which we live when it comes to body shape and composition. On one hand, we are bombarded with images of super lean models and film stars making amazing body transformations in preparation for a new super hero role. On the other hand, we have the body positivity movement, which focuses on the acceptance of all body types, regardless of size, shape, skin tone, gender, and physical abilities. Although in many ways such an accepting attitude is to be applauded, it has led to the increasing presence of obese models in the media, which tends to normalise obesity. At the same time, there is an ever-growing amount of research showing how potentially harmful excess body fat can be.

These mixed and misleading messages can lead to confusion regarding what we should eat, and what is a healthy body shape. People can feel dissatisfied with their normal, healthy body, which can lead them to resort to potentially unhealthy dietary practices and unsafe exercise regimes. Alternatively, they may feel that is not necessary to address being overweight and accept their body shape without fully appreciating its associated risks.

Social Media

Social media can have particularly pernicious effect on our perception of body image. A study by the Royal Society for Public Health, which investigated the effects of social media, found that Instagram was the most damaging social network for mental health, affecting anxiety levels and body satisfaction, as individuals compare themselves to unrealistic, filtered and Photoshopped versions of reality. It was also associated with high levels of depression and bullying (1).

Here at Time 4 Nutrition, our main priority is health, and we take an evidence-based approach to the supplements we produce and the information we provide. We understand how damaging the conflicting and confusing messages propagated by the media can be. So, in this article we are going to look at what the science tells us is a healthy body shape and body composition and assess how realistic many of the claims in the media are.

Body Fat

Body Positivity Versus Science: The Dangers Of Too Little Or Too Much Body Fat

The recent Covid crisis has helped to highlight the potential health risks of obesity. For example, for people with a body mass index (BMI) of 35 to 40 (obese), the risk of death from COVID-19 increases by 40% and with a BMI over 40, by 90%, compared to non-obese patients. Additionally, very obese individuals (BMI 40+) were overrepresented in intensive care by approximately 300%.

As disturbing as these statistics are, the consequences of excessive body fat go far beyond Covid and include an increased risk of:

- All-causes of death (mortality)

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides (Dyslipidemia)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Coronary heart disease

- Stroke

- Gallbladder disease (gallstones, gallbladder inflammation)

- Pancreas (increased insulin, type 2 diabetes)

- Bones (osteoarthritis and gout)

- Kidney problems (renal cancer, kidney stones)

- Bladder problems (cancer, bladder control issues)

- Sleep apnoea and breathing problems including asthma, mechanical ventilator constraints

- Certain cancers (endometrial, breast, colon, kidney, gallbladder, prostate, and liver)

- Menstrual irregularities

- Complications with pregnancy

- Problems receiving anaesthetics

- Mental illness such as clinical depression, anxiety, and low esteem

- Body pain and difficulty with physical functioning

- Low quality of life (social stigmatisation and discrimination)

- Premature death (2, 3, 4, 5)

While the health risks associated with too much body fat are well acknowledged, those associated with too little are less so. These include an increased risk of osteoporosis, bone fractures, muscle wasting, abnormal heart rhythms and sudden death, as well as kidney and reproductive disorders (5). Additionally, those with too little body fat tend to be malnourished. Consequently, it’s important to maintain a healthy level of body fat.

How Much Body Fat Should We Have?

Body Positivity Versus Science: This Brings Us To The Question: How Much Body Fat We Should Have?

Although too much or too little body fat is considered unhealthy, there is no universally accepted consensus regarding the amount of body fat a person should have for optimal health. This is because it is likely to vary between individuals and is influenced by a number of factors, including race, gender and age. As a general guideline, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) suggests that a range of 12-23% for men and 17-26% for women is considered ‘good’ (2).

However, it is important to be aware that a bodybuilder or an actor may reduce their body fat levels to just few percent for a competition or film role, but this may have taken many weeks or months of strict dieting and intense exercise to achieve, and is unsustainable in the long-term.

Similarly, athletes when in competition may achieve very low levels of body fat depending on their sport. For example, elite male marathon runners have been shown to possess fat levels as low as 3.3%. While some individuals have the genetic predisposition to maintain very low levels of body fat, for others it is a struggle that is only achieved through unsustainable and unhealthy restrictive dieting.

Body Positivity Versus Science: What Is A Realistic Rate Of Fat Loss?

The media is full of amazing rapid weight-loss and body transformation stories, but what does the science tell us is a safe, effective and sustainable rate of weight loss?

Regardless of how much weight you ultimately want to lose, your initial fat loss goal should be to reduce your body weight by no more than 5-15%, unless otherwise directed by a medical professional (3).

The reason for this modest goal is that setting targets greater than 5-15% has been shown to result in unachievable expectations and, consequently, failure (3). As a general guideline, you should aim to lose 3-10% of initial body weight over a three to six month period at a rate of 0.5-1 kg (1lbs to 2.2 lbs) per week (4, 5).

The most effective way of achieving this is to create a daily energy deficit of 500 – 1000kcal, which produces a weekly shortfall of 3500 – 7000kcal.

In order to minimise the loss of muscle mass, research suggests that we should limit our weekly deficit to approximately 3,500 kcal or 500 kcal per day (4).

The results of a study by Mayo et al (6) showed that although energy deficits greater than 700 kcal/day, produce greater weight loss, they also result in a greater loss of muscle. Consequently, if you wish to lose 10 kg, you should allow a period of approximately 20 weeks to achieve this.

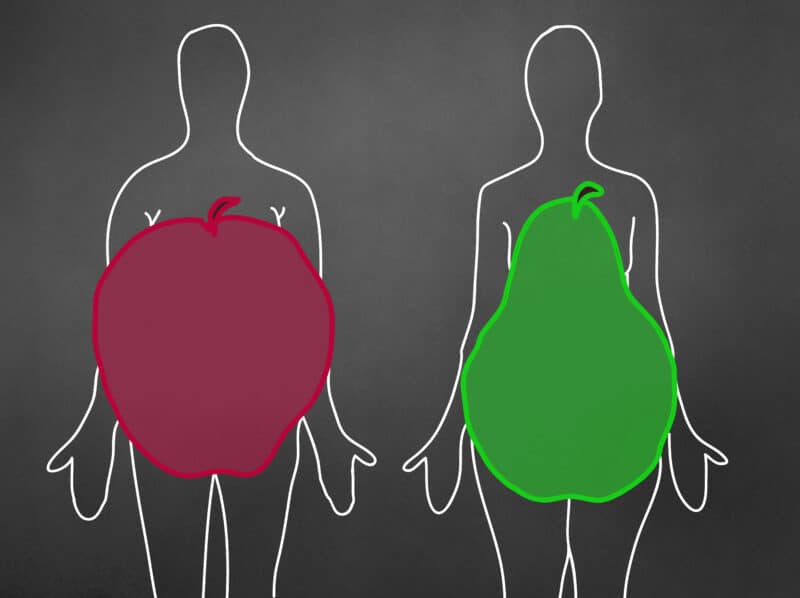

Body Positivity Versus Science: Defining A Healthy Body Shape: Are You An Apple Or A Pear?

We probably all have an idea of what we think a healthy body shape is, but it is important that we do not to confuse what we think is attractive, which is matter of individual taste, with what the science tells us is healthy.

Where we store fat on our body it appears to have a greater influence on the health risks associated with obesity rather than our total amount of body fat (5).

Individuals with android obesity (apple shape), in which fat is mainly deposited on their trunk (abdominal fat) have a greater risk of suffering from obesity related conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease, etc, compared to individuals with gynoid obesity (pear shape), in which the fat is deposited on the hips and thighs (2). This is because abdominal fat is not only limited to the layer located just below the skin (subcutaneous fat). It also includes visceral fat, which lies deep inside our abdomen, surrounding our internal organs (3). An excessive amount of visceral fat produces hormones and other substances that can raise blood pressure, negatively affect blood fat levels and impair the body’s ability to use insulin (7). Visceral fat is more responsive metabolically than the fat stored in the hips and thighs. Therefore, it is more likely to be broken down and lead to atherosclerosis, heart disease, etc (3).

Android obesity is more typical in males while gynoid obesity tends to be more typical in females. However, some men have gynoid obesity and some women have android obesity (5). Typically, men’s abdominal fat tends to increase progressively with age. Women tend to gain more fat on their abdomen after the menopause, when fat tends to shift from the arms, legs and hips to this area (7).

Body Positivity Versus Science: Waist-To-Height

A simple way to find out if you have healthy body shape is by simply measuring your waist.

A study by Ashwell et al., (8) analysed the health of 300,000 people, and found that the ratio between our height and waist was a better predictor of high blood pressure, diabetes and cardiovascular disease than BMI.

Ideally, we should aim to keep our waist measurement less than half that of our height (9). For example, a man 6ft (182.88 cm) tall should aim to keep his waist less than 36 inches (91.4 cm), while a 5ft 4in (162.56 cm) woman should keep hers under 32 inches (81.28 cm).

Body Positivity Versus Science: Equal But Different: Gender Differences In Body Composition

More recently there has been an increase in images of extremely lean women sporting ‘six packs’ any man would be proud to possess. However, in terms of health, a woman typically needs more body fat than a man. To understand why this is, we need to look at where we store fat and what it does.

Body fat is primarily stored in two sites referred to as essential fat and storage fat.

- Essential Fat consists of the fat found in the marrow of bones, the heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, intestines, muscles and the tissues of the central nervous system, which is essential for normal physiological functioning. Women have sex specific essential fat found in their breasts, pelvic, thigh and buttock regions, which is important for hormonal functions and child bearing. Women have approximately four times the amount of essential fat than a man (12% body mass for women compared to 3% body mass for men) (4).

- Storage Fat consists mainly of fat in adipose tissue. It includes the fat that protects the organs within the chest and abdomen from trauma, and the subcutaneous fat (fat beneath the skin). Men and women have similar proportions of storage fat (12% of body mass in men and 15% in women) (4).

Note: A certain amount of body fat is believed to be important for ensuring healthy menstrual function. It has been suggested that 17% body fat is the lower end necessary for the onset of menstruation with 22% needed to sustain a normal menstrual cycle. However, various studies have shown that female athletes may have body fat levels below the proposed critical level of 17% but still have normal menstrual cycles (4).

To learn more about body fat and how to achieve healthy levels, just click here to access our free evidence-based series of articles on the science of fat loss.

Body Positivity Versus Science: Fact Versus Fantasy: What Are Realistic Muscle Gains?

The media is often more about fantasy than fact, and will employ every means to produce images of ‘godlike’ perfection. So, claims by celebrities, such as losing 10kg of fat and gaining 10kg of muscle with a diet of chicken and broccoli in a few months should be viewed with some degree of scepticism.

As we have seen, losing fat requires a calorie deficit, while on the other hand, building muscle requires a calorie surplus above normal daily energy needs (As a guide, you should start conservatively with an energy surplus within the range of 350 kcal 500 kcal per day).

Although those new to exercise will initially lose fat and gain muscle relatively easily, this rate of progress soon slows or stops. Consequently, bodybuilder’s, the masters of changing body composition, will typically divide their training programme into two basic phases. These are a building or ‘bulking’ phase, where the focus is gaining muscle, which tends to be accompanied by an increase in body fat. This is then followed by the ‘cutting phase’, during which the aim is to reduce body fat levels dramatically while maintaining as much muscle as possible. Both of these phases involve specific dietary and training approaches and often employ the use of specific drugs.

That said, some individuals possess the genetics which allow them to make remarkable gains but they are very rare.

As a rule, if you’re new to resistance exercise, you can expect to begin to see an increase in muscle after 15 training sessions, or 6–7 weeks, and expect to gain on average 3lbs (1.36kg) of muscle after approximately 3 months of training (3).

A study involving young athletic men found that a one-year programme of heavy resistance training produced a 20% increase in body mass, most of which was muscle (3). It is important to note that the rate of muscle gain rapidly plateaus are the first year of training and that young men have high levels of the muscle building hormone testosterone. Athletic women can expect to gain 50-75% of the absolute gains of men in their first year of training (3).

Body Positivity Versus Science: Muscle: Can You Have Too Much Of A Good Thing?

Unlike body fat, when it comes to muscle, there has been a tendency to think more is better, but research is emerging to suggest that this not true and, like fat, excessive amounts of muscle may also be potentially dangerous.

Body Mass Index has typically been used to assess an individual’s weight related health risks.

This is a mathematical formula used to determine a person’s weight relative to their height. It is calculated by dividing body weight in kilograms by height in metres squared (w/ht2) (3).

For example, if you weigh 70kg and are 1.75m tall you will have a BMI of 22.9.

BMI = 70 kg / (1.75 m2) = 70 / 3.06 = 22.9

It is used to classify people as underweight, overweight and/or obese.

As a quick guide you are considered to be:

- Underweight if you BMI is less than 18.5

- Normal weight if your BMI is 18.5-24.9

- Overweight if your BMI is 25.0-29.9

- Obese if your BMI is 30 or greater (4)

It is important to note that what is considered a healthy BMI varies by race.

Although BMI is inexpensive, simple and quick and is useful as a population-level measure of being overweight and obese, it does have its limitations such as overestimating the fatness of people that are very muscular, such as body builders.

Consequently, the main argument against the use of BMI (Body Mass Index) for those carrying a large amount of muscle mass is that it is an excess of bodyfat that is harmful to health not being heavy per se. However, in recent years concerns have been raised in the bodybuilding community over the potential health consequences of carrying extremely high levels of muscle mass as exhibited by some modern bodybuilders, despite their low levels of body fat.

It seems that there is some scientific evidence to support this concern. A study by Ortega et al., (10) found that having a very high BMI was a significantly stronger predictor than a very high percentage of body fat on cardiovascular mortality. The authors concluded that despite BMI being a poor index of body composition, because it does not discriminate between fat mass and fat free mass (i.e., all tissues that are not fat including muscle, bone, organs), it is perhaps a very good index of future health/disease, and particularly for cardiovascular disease. The explanation for this finding seems to be related to the fact that a very high level of fat free mass was also positively associated with a higher risk of CVD death.

To learn more about the safest and most effective ways of increasing muscle mass, just click here to access our free evidence-based series of articles on the science of building muscle.

Body Positivity Versus Science: Conclusion

The point of this article has not been to berate people for their lifestyle choices but to highlight the disparity between what the science says is a healthy body shape and composition and what the media portrays, which can lead to misconceptions about what is healthy and cause people to result to potentially harmful diet and exercise regimes. It is important to understand that flattering lighting, make-up and digital enhancement are all used to produce an image of ‘perfection’. Even if a person has actually achieved a certain physique for a film role or photo shoot, they often cannot maintain such a condition in the long-term. It is quite easy to find unflattering pictures on the internet of actors and celebrities ‘off season, and looking quite different to the fantasy they portray on screen. Yet such images are rarely publicised.

While beauty is in the eye of the beholder, health is not. The evidence is quite clear that excessive amounts of body fat or muscle, or too little, increase the chances of numerous health conditions and premature death. However, vilifying and bullying people about their weight is not the right approach to address this issue. Not only is it morally and ethically wrong, but the science tells us that it is likely to alienate people and perhaps even exacerbate the problem as they result to eating as a source of comfort.

So, what is the right approach? Ideally, society and the media should aim to educate people as to what is healthy and provide them with the knowledge, skills and support to make the requisite changes. There’s nothing wrong with fantastical images of physical perfection providing we understand that they are, in most cases, just fantasy.

We also understand the importance of having the right mind set to achieve successful long-term health and fitness goals. To this end, we have commissioned a series of articles on mental health and behaviour change by PHD Psychologist Dr Pat Partington.

You can access all of this information and much more for free at